All Paths Lead From Here - A Very Brief Introduction to Permaculture Design

Originally shared as a presentation at Arts Council England's Creative People and Places gathering which took place in Barrow In Furness on the 5th and 6th June 2024.

I am not sure how I first came across permaculture design but am aware of it starting to come into my life around the mid 2000s, a time which coincided with a move to a house where I finally had my own small garden and, soon after moving, an allotment.

At that time I was working for the Library Theatre Company in Manchester as the Community and Education Director. Although I loved my work I felt a growing disconnect between it and an increasing worry and fear that I had about the climate crisis. Working creatively in the inner city I was deeply nourished in many ways but there was a strong pull to reconnect my life to the land somehow. I wanted my hands to be in the soil and my allotment was the initial catalyst that began a personal journey of discovery and connection towards this.

Through growing and tending my understanding of permaculture began to emerge. As many people do I thought it was all about gardening so I dabbled at the edge in self led learning, and using what I had learned I began to create a beautiful, abundant, wild growing space.

It wasn’t until a little later in 2011 that I finally embarked upon some more formal permaculture learning. This took the form of a Full Permaculture Design Course convened by Angus Soutar in Lancaster. For a year I spent one Saturday a month up there on a community allotment on an estate just outside the city centre. Over these twelve months my mind was blown and my life was changed. Having joined the course to design my allotment I was amazed to discover that permaculture wasn’t just about gardens and growing. It offered a whole new ethically based set of tools and frameworks that had been created to help us think about how we can live in ways that redesign and re-imagine our impact on and connection to the planet. Ways that might allow us to make a place for ourselves in days to come where we may once again become part of the continuous and never ending emergence of a single moment in time.

So where did this idea of permaculture design begin? The original thinking lay with the biologist Bill Mollison in the 1950s. Whilst observing marsupials in the Tasmanian rainforest as part of his work he noted that he was “inspired by the life giving abundance and rich interconnectedness of the eco system” He went on to note “I believe that we could build systems that would function as well as this one does.”

By the late 1960s Mollison had taken these ideas further and had started developing ideas about sustainable agricultural systems motivated by increasing concerns that he had about the ways that he was observing industrial agricultural methods destroying local ecosystems.

It was not until 1974 that he finally met the co-originator of permaculture design, the landscape designer David Holmgren”, and the term “permaculture” emerged. This happened in relation to sustainable food-growing systems that they had developed based around perennial food crops with the word originally intended as a contraction of “permanent agriculture”. However Mollison quickly realised that what he was actually interested in was the creation of a system for the development of “permanent culture” acknowledging that unless humans were able to do that no culture would survive.

Through the exploration of sustainable agricultural methods they realised that what they wanted to create was an integrated systems approach to sustainable living whilst asking ourselves:

“how do we live with the least effort for the optimum effect?”

Or:

“how do we create the greatest abundance whilst causing the minimum impact?”

It was from these original explorations that Mollison’s prime directive of Permaculture Design emerged. The idea that:

“the only ethical decision is to take responsibility for our own existence and that of our children.”

And at the same time the core provocation took shape: the idea that the best way to creative regenerative ways of being is to think in terms of the complexity of systems and wholes, to come from a clearly defined ethical foundation of earth care, people care and fairshare, and to look to the natural world, and by association traditional ecological knowledge, as all the answers that we might need already exist within the incredible abundance and diversity of nature. This balance of ideas brought together by Mollison and Holmgren was then, and is now a unique provocation within industrial society.

It is of course essential to reinforce that this proposition was not a new one, nor would Mollison or Holmgren have ever claimed that it was. Instead it marked a moment of realisation and rediscovery within industrialised societies such as our own of ways of being that have been honoured and held all over the world by indigenous cultures throughout human existence. We are here today because throughout history most of our ancestors have lived in regenerative ways, as part of a planet where life-giving systems have managed to persist for 3.7 billion years.

To our current knowledge ours is the only planet in the universe where such conditions exist.

Life here is a regenerative impulse and permaculture design helps us to explore how we can align with this impulse once more. How we can be truly responsible participants in something that we can’t control but that we can dance with.

It is no surprise to me that for Mollison and Holmgren this journey started with growing food as that is the same way that it starts for many of us. Like the way it started for me with my allotment. This is because food is central to our lives and connected to every aspect of how society is built. When we consider how to grow food we soon appreciate that everything is connected and that we can’t have healthy food without good soil, clean air, clean water… By growing even a small amount of food we realise that it is sometimes possible to do things that disentangle us, if only for a moment, from the industrial world that feels almost inescapable.

In its simplest form permaculture is the idea of a new regenerative culture and permaculture design is a set of tools that we can use to create that culture. But what do we actually mean when we use the word regenerative?

In the dictionary on my bookshelf at home there are two different definitions. The first one says:

“relating to something growing or being grown again”

and the second says:

“relating to the improvement of a place or a system, especially by making it more active or successful, or making a person fell happier and more positive.”

Of these two the first one feels more resonant within a permacultural context thinking about notions of the continual growth and re-growth that occurs constantly in natural systems.

The second is connected more to the way that the word “regenerative” is often used in relation to place making and development. The sense of this is significantly different to the idea of a continual, organic, emergent process implied in the first in relation to the regenerative processes. So the first definition feels more relevant in terms of what we are looking to in permaculture design.

The next definition that I came to which really resonated was created by The RSA as part of their Regenerative Futures programme – an ongoing body of work exploring ways to create a future where people and planet flourish hand in hand for the long term:

“A regenerative mindset is one that sees the world as built around reciprocal and co-evolutionary relationships, where humans, other living beings and ecosystems rely on one another for health, and shape (and are shaped by) their connections with one another. It recognises that addressing the interconnected social and environmental challenges we face is dependent on rebalancing and restoring these relationships.”

I love the way that this definition places the idea of connection at the core of the regenerative, highlighting the reality that it is impossible to be disconnected within an entangled universe.

To take this thinking further it is useful to look at the idea of regenerative in relation to other words that we may be familiar with : extractive, sustainable, and resilient.

The image to the left represents “extractive” with the axis on the left representing resource availability, and the one on the bottom representing time. Within extractive systems resources are depleted through processes that take but don’t give back. As a result of this the systems loses capacity over time. The climate and ecological crisis is as a result of sustained and continuing period of extractive behaviour / culture

The next image represents “sustainable”. Within sustainable systems resource availability is not depleted over time so the system is steady. It is about preservation and not restoration, and this is a challenging concept on a planet that is already deeply damaged. Sustainable is not bad in itself but it is difficult to continue in isolation – for example doesn’t allow for the unexpected or periods of shock as there is an absence of restorative growth.

The third image represents “resilience”. Within systems “resilience” refers to the in built mechanisms that exist within ecosystems that allow the system to recover from periods of shock. For example a forest is able to recover from forest fires occurring at a natural rate as a result of inbuilt resilience within the ecosystem. Again this can’t function in isolation – for example, if a system is simply sustainable each time it suffers a shock it will be able to continue but it will be slightly depleted.

The final image represents “regenerative”. Here resources grow and are regenerated at a rate that allows a system to build capacity so that it is able to be resilient to periods of shock. This is based on sustainable growth and interconnected patterns of loss and restoration. In this sense system can only be sustainable if it is also regenerative.

This is when we arrive at the challenge of the regenerative. When we look at natural systems such as a forest or a pond it is easy to define what regenerative looks like because of things the way that it sustains itself as a whole without intervention and with health and abundance based on relationships of reciprocity. By association it does not involve a huge leap to begin to imagine and understand regenerative agriculture systems, but it isn’t just food systems or green spaces that need to be regenerative… It’s absolutely everything.

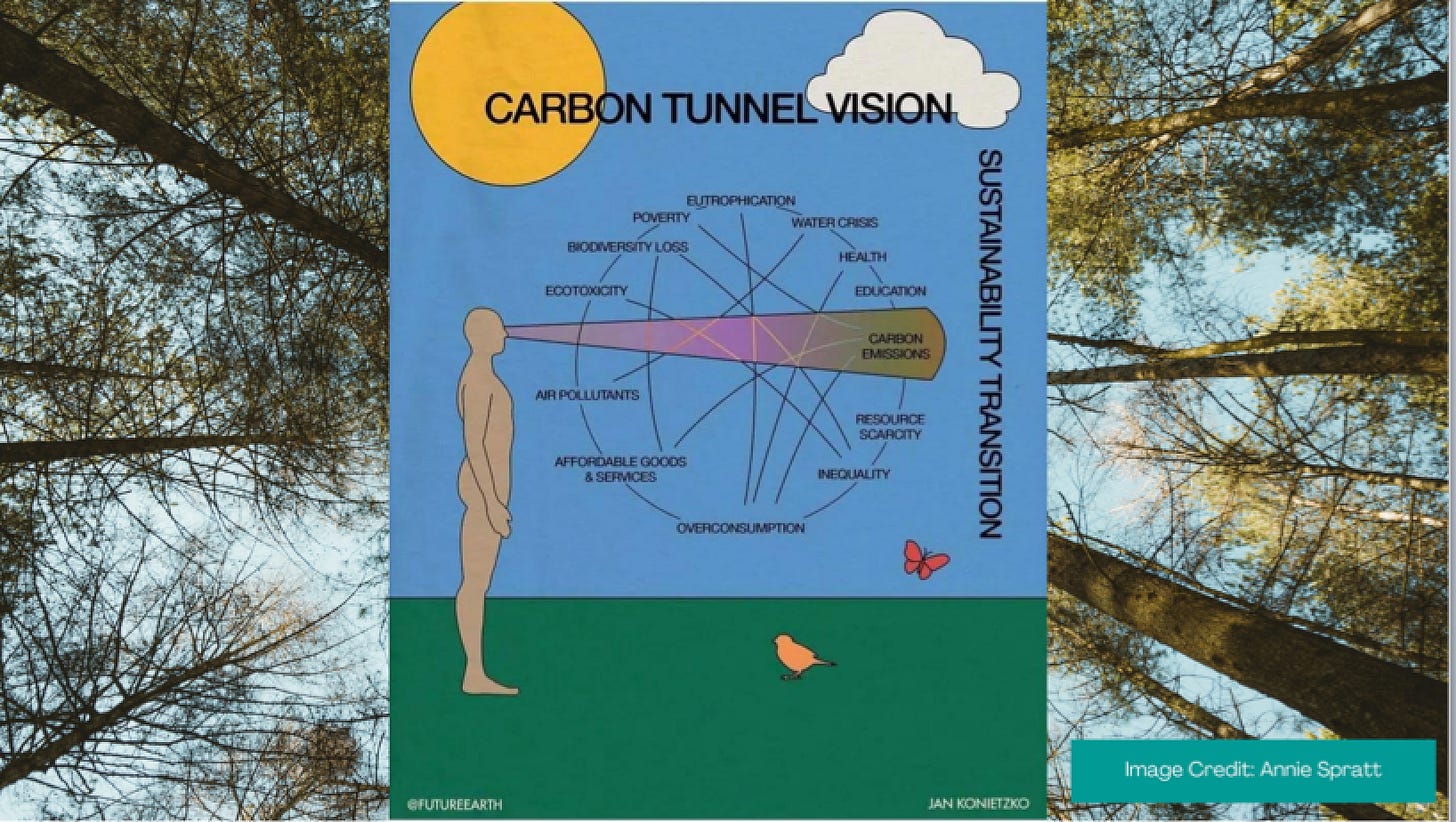

So what might a regenerative school look like, or hospital, or theatre, or arts organisation, or business look like? That is much more complicated and much harder to imagine. And what might these regenerative ideas mean in terms of our response to the climate and ecological crisis? If we acknowledge the entanglement of challenges that converge within it at this moment in time we soon realise that a single response such as carbon reduction will not provide an escape. If we could remove all carbon by magic tomorrow we would still be left with over consumption, biodiversity loss, air pollution….etc…etc….

In thinking about this I am drawn to the quote by regenerative thinker Carol Sandford:

“Life conducts itself in nested reciprocal systems, within which each life form plays a role that contributes to the working of the overall whole.”

So how may permaculture design help us in relation to this when thinking about arts practice and cultural organisations?

Permaculture design is a set of tools that can help us find our true place within in the complex, connected systems that Carol Sandford is talking about. It is a set of tools that can help us become creatures of place one more, and that help us feel like we belong in complex, reciprocal ways. It can also help us to rediscover the instinctive understanding of living wholes embedded in our species in the form of ancient cultural and spiritual wisdom

So what does that mean in practice for different organisations and partners that I have been collaborating and creating with? I am going to share five different examples of organisations / projects who have been exploring how they might use permaculture design and ideas to help shape the work that they are doing and / or their structure going forward.

The first example that I am going to share is my own creative practice. Following on from my Permaculture Design Course I embarked upon a Diploma in Applied Permaculture Design supported in the first instance by Hedvig Murray, and later by Carla Moss.

The diploma was about creating a portfolio of designs using the skills that I have learned in my PDC. For me this became a space where I explored how I could bring all aspects of my life to better understand them as a connected whole. In doing do so I wanted to explore how I could better play my role in contribution to the whole that is our planet motivated a growing sense of responsibility that I felt in relation to my participation on this moment of planetary ecological crisis.

When I started this journey I felt that my life was made up of many disconnected roles and responsibilities that were often in contradiction and conflict with each other. The journey of my diploma helped me better understand the entangled ecosystem of my own life and then the larger entangled, messy wholes that this is part of.

But what has this meant on a practical level in terms of my arts practice, and by association by life? It has taken many different forms in terms of reconnecting to my own local community, refocusing the work that I do, and trying to think about the way that I as an artist and creative can therefore be best engaged in this moment of huge change that we find ourselves as part of.

Through the learning within my diploma I began to deepen my practice in a way that focused around amplification of care starting with myself grounded in the permaculture ethics of people care, earth care, and fair share.

My permaculture design practice has been central to this but it is important to note that in many ways permaculture still very much focused on land and landscape design so a big part of this journey has been growing in confidence to think how we can take land focused tools and frameworks to shape them to help us create other things. For me those other things that I have particular interest in are arts practice and culture in terms of the work that we create and share, but also in terms of the structures that support that work. Alongside this I am interested in the value and energy that the creativity and imagination that artists and creatives, and creative organisations can bring to the movement and practice of permaculture as a whole.

LeftCoast delivers highly-engaging and socially-useful arts and cultural projects in Blackpool in Northern England. In the middle of 2023 the core team Initially engaged formally with permaculture design through a one day training session for their core team which introduced the ideas of permaculture design, and began exploring notions of what regenerative may mean from their perspective.

However, this wasn’t the beginning of ideas related to permaculture. This began to emerge in 2021 through a number of different artist residencies. The first was a residency undertaken by Niki Colclough which took place on Bostonway Housing Estate as part of the Real Estate Residency programme. During her residency, Niki studied the trees in Bostonway and joined locals in an urban forest bathing sessions. Residents were encouraged to engage with the nature on their doorsteps.

A little later Gillian Wood turned her garden in Fleetwood into a growing space as a way of engaging through Covid lockdowns. And Sarah Harris developed growing projects, again in Bostonway. Laura from Left Coast described this as being a groundswell of similar themes, closely aligned to permaculture, that all came to the fore at the same time.

Following on from this they began to explore permaculture more explicitly leading to the development of an artist residency At The Grange in early 2023. This was outlined to “ build on the activity happening in the space to experiment with and further embed permaculture principles in their widest sense.”

Permaculture ethics and principles had a natural alignment to work that LeftCoast were doing and bringing them more consciously into their processes and work has helped inform problem solving and decision-making. One particular progression of the journey has focused upon supply chain and doing this has enabled space for more regenerative ways of working to emerge themselves. For example, in summer 2023 when working with a large scale installation created by Morag Myerscough that toured 3 neighbourhoods, the discussion about what to do at the end with the materials was had and agreed from the outset. Work would be created in such a way that volunteers and community partners could be gifted back signed parts of the artwork for their own use. As a result of this the waste from the project was minimal.

In January 2024 decisions around materials used was integral to the One Pot Community Food project. Within One Pot fifty families across the local community were gifted with a slow cooker, cooking utensils, recipes, and the ingredients to make them. In exchange, participants donated recipes to a community cookbook, attended a live cooking session and creative workshops, and spent time volunteering at other projects. These multiple invitations to participate allowed the project to move from a typical food bank model to a co-created project where each participant became part of an exchange that was accessible to everybody.

There was a determination not to use plastic and this shaped the way the project developed. It was decided at the outset that participating families would be given a tote bag to carry their ingredients home each week. When people forgot their paper bag they were given a paper bag. It was soon discovered that these are not good at carrying things home in the winter rain in Blackpool and they then broke on the way home! Meant people brought tote bag next time so new habits began formed around waste and reuse,

Left Coast is also embedding permaculture thinking within the board through the ethics, and using permaculture tools to reflect after board meetings. This is helping to grow a cycle of reflection and developlment within the organisation around regenerative ideas.

Whitechapel Art Gallery is a gallery located in the East End of London focused upon making contemporary art and ideas accessible to the widest possible audiences. Kirsty Lowry, Schools Curator, had been drawn to permaculture ideas, particularly the design principles, to start exploring participatory work with locally schools focused upon nature. Kirsty participated in the Introduction to Permaculture for Artists and Creatives to inform that work, and to develop the programme and better articulate the shift that she hoped to achieve.

Supported in part by this learning Edge Effects has become a participatory project that takes inspiration from nature to shape an ongoing series of artist residencies with primary and secondary schools in Newham, East London. The project has adopted a slow approach, guided by principle of permaculture to observe and interact. Out of these workshops an exhbition was created which was supported by a guide featuring an introduction to Holmgren’s 12 permaculture principles A particularly rich yield of the project has been the wider conversation that is has inspired around the way that the gallery develop and deepen their relationships with local schools as different elements of a whole eco system.

Heart of Glass is a Merseyside based community arts organisation. I had previously had contact with member of team, Kate Houlton, through another permaculture focused project developed by Manchester International Festival in 2013. This contact was rekindled by Kate when her and another member of the Heart of Glass team participated in an Introduction to Permaculture for Artists and Creatives in April 2023. The course was convened by Hannah Gaunt of Engage, the leading charity in the UK for promoting engagement and participation in the visual arts.

In participating natural alignment became clear between ideas at driving their work and the ethics and ideas at the core of permaculture design. This led to my participation in their annual conference With For About: Care and the Commons in May 2023 facilitating a workshop about the permaculture ethics.

Since then Heart of Glass have been exploring how permaculture can be used as a way to help articulate ideas and drive forward the work that they want to do. In the first instance this exploration took the form of training for staff team and board in permaculture, cultivating a shared language across the organisation.

The next step was to being exploring ideas of what regenerative may mean in terms of the organisation, and also where practices may be particularly extractive. Out of this several elements developed for example thinking about rest and how work may be structured to explore this in relation to seasonal patterns and down time.

They are also looking to embed thinking more deeply through development of a Permaculture Sub-Group. The starting point for the group will be to think about the ways that permaculture might inform development of policy documents and action plans, initially focusing upon Equity, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion and Environmental action plans. The intention is that the permaculture ethics of People Care, Earth Care and Fair Share as core themes for exploration. The aim is to continue ensuring plans are on target and ensuring Heart of Glass are meeting reporting requirements but also to think more expansively exploring how these permaculture ethics may be embedded across all areas of operation.

Lyth Arts Centre is Scotland’s most northerly mainland arts centre, presenting an annual programme of live performance across Caithness alongside contemporary visual art and an extensive participatory programme of educational and socially- engaged arts projects led by local creatives in their community. Their director Charlotte Mountford initially participated in Introduction to Permaculture Course then joined the first cohort of the Full Permaculture Design Course for Artists, which I convened in 2023. This unique 72 hour course took the classic Permaculture Design Course as a starting point, and created a learning community of 22 artists who learned and deepened their permaculture design skills so that they could start to bring a truly regenerative focus to their work

As part of the course Charlotte used the design project to focus upon the development of a consultation process for the Future Feasibility study of the organisation, with particular focus upon where their home may be. The design explored the question ‘what is an arts centre for the future in Caithness?’, and used permaculture tools and ethics to explore how could move away from culture led regeneration to a focus on regenerative practices

The design is currently being implemented and is an emergent exploration will likely expand and develop going forward. Chartotte noted that using permaculture design has made it easier to incorporate co-design processes and feedback loops bringing a real live-ness and sense of energy to the whole.

That’s the end of the formal part of this presentation. I have loved sharing this time with you and feel excited about the connections and abundances that will emerge as a result.

Before we open the floor to questions and reflections I would love to end by sharing a story shared by the brilliant Dougald Hine shared as part of a course that he convened last year and which is also shared in his book “At Work In The Ruins.” He heard the story off Sarah Thomas, and she heard it off the Tyson Yunkaporta. Nobody is sure where Tyson heard it from – maybe the land itself.

Tyson says that in the best of worlds we stand at the beginning of a process of shared planetary healing that will take at least a thousand years, because that is how long it will take for the old growth forests to return, how long it takes for the mother trees to grow back.

Dougald pointed out that Tyson is a great storyteller so he knows what an ask this is.

In Dougald’s words:

“There is something quieting about the invitation contained in such a story. It is hardly a promise that this will come to pass and it does not deny the urgency of all that we should be doing – or not doing – in our own life times. It asks me to imagine that my kind may be part of the process by which forests flourish. That this is part of what we have been, that it is part of what we can still be.”

To me the true power of permaculture design is that it allows us to believe that this transformation is possible, and it helps us to begin creating and imagining new (or maybe old?) ways to begin.

Liz- Thanks for sharing this. Now if only I'm in the UK, it would make things so much easier. Hope you're well this week. Cheers, -Thalia

I have just recently read at work in the ruins and it makes so much sense with connection to how we may make use of our time. Regeneration also has an unpredictable edge to it - we can never fully know what will manifest and what changes it will bring and I think in a prescriptive time it's not been something that sells easily as we can't own the results. Loved reading this and all the projects being influenced by permaculture